52 Countries in 52 Weeks, Part 27: India

In Which I Have A Rewarding, Challenging, Beautiful, Exhausting Two Weeks Unlike Any Other This Trip (And Also Dance Badly)

“Are you from Surrey?”

If I was anywhere else in the world, it would be a tremendously weird question to be asked by the 20 or so tweens that excitedly surrounded the geeky foreigner with a strange accent.

Surrey is the second largest city in the Canadian province of British Columbia, but because of its position as a suburb community next to Vancouver, gets very little international attention.

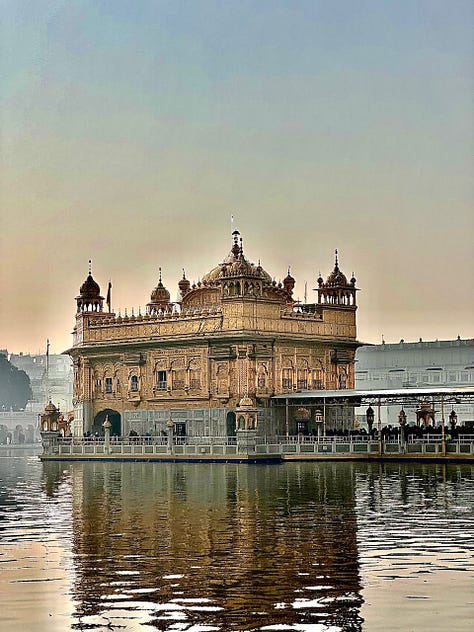

However, I was in the one international place where Surrey would be considered a hotspot: Amritsar, India.

That’s because Amritsar is the centre of the Sikh religion, and hundreds of thousands of Sikhs have immigrated to Canada over the last four decades — with Brampton, Ontario and Surrey, B.C. the two biggest centres.

It means that around 1 in 10 people in Metro Vancouver are Sikh, the highest proportion outside India in the world. And because it was important to understand that connection a little better, I had found myself in a kitschy but undeniably authentic heritage theme park on the outskirts of town on day 272 of my journey.

Which is why, after answering their first question with “Canada”, I got their Surrey excitement.

Somehow, they didn’t really care about my attempts to show them the geography of Metro Vancouver while explaining I was *near* Surrey but not *from* Surrey (I truly cannot help myself). What did interest them, however, was trying to get me to dance with them in the faux temple.

I, uh, am not comfortable dancing.

Still, they seemed sincere in their desire to share a funny moment.

And so I made a deal with them: I would dance for a couple minutes in the faux temple, if they agreed to take a little selfie with me.

I was happy to have such a random and organic moment of connection.

But I’m even happier that no footage exists of my dancing.

You can’t travel the world for a year and not go to India.

I mean, I suppose you could skip it and still have plenty of valuable cultural experiences.

However, you’d be missing out on the most populated country on earth (it eclipsed China in estimates in 2013), one of the cradles of civilization, a stunning (if often messy) mosaic of diversity, an ongoing test case in democracy and industrialization at a scale unseen in history, and an endless array of things to see and do and eat.

So there was no question I wanted to see India. The bigger question was whether India wanted to see me.

While I was in the midst of planning my trip, Canada-India relations took a nosedive following the targeted killing of Hardeep Singh Nijjar, a Surrey resident and pro-Khalistan activist.

The two countries disagree, to put it mildly, over whether the Indian government was involved in his murder, which temporarily resulted in the temporary suspension of India issuing new visas to Canadians, along with Canada expelling Indian diplomats six weeks before I was set to arrive.

Adding to my anxiety, the Indian government has a very strict visa policy for journalists visiting even for tourism, with a difficult process to complete remotely during the course of my travels, and which often results in declined applications.

Still, I made it through. I navigated the short taxi to my Delhi hotel, one of dozens along a chaotic strip next to the airport. And aside from a terse conversation with a tour guide who insisted that Canadians are allowing Sikhs to burn Indian flags on every street corner, politics left my mind once I arrived.

It was time to be exhilarated. It was time to be exhausted.

Here’s the best way I can put it: India was one of the most challenging countries that I’ve visited on this trip, but also one of the most rewarding.

Yes, I know, this could easily turn into your 2,000th basic white tourist earnestly writing “I saw a slum and it was sad but the people are so kind and the temples are so beautiful that i felt wisdom and grew out my hair and got a tattoo, namaste,” and I promise (or at least hope) that my feelings are a little more complex and a lot less condescending than that.

So here’s a little breakdown from my perspective on why exactly India is both challenging and rewarding, with observations that are a little bit more granular, and hopefully helpful for anyone thinking of visiting.

Challenging: transportation. India has a very extensive train system, which unfortunately is very old and very overcrowded with many trains that end up being hours late. Additionally, the government’s booking system is incredibly byzantine, with approximately 782 classes of ticket that become available at 42 different time periods.

The airline system is better, but there are still delays and far fewer destinations available. The buses are plentiful but often bumpy, while taking a taxi or Uber or car will take you twice as long as an equivalent distance in most countries. Metro systems are being built up in Mumbai, Agra and other cities, but for the moment only Delhi has a fully functioning one, and it requires foreigners to line up to pay in cash at each station for each ride.

In short, it will take more time and more planning to do specific things in India, and you will sometimes feel frustrated.

Rewarding: geography. The old Mercator projection maps, the ones that make Greenland look so big that Donald Trump gets strange ideas, do India dirty.

The country is 3.3 million square kilometres big, 7th largest in the world, equivalent to 80% of the European Union in size, with six distinct zones and 28 states that all have different mixes of climate and religion and history and culture.

More than that, because of the shifting nexus of kingdoms and movements throughout the century, there’s no one place that is most obvious and interesting to visit.

In some ways, this plethora of riches makes planning a challenge: in other big countries where I spent multiple weeks, there were clearly 2-3 key places to visit, and I could fill in the rest based on my pet interests.

For India, I was filled with what ifs: in my 17 days there, I ended up doing the “Golden Triangle” of Delhi, Jaipur and Agra, along with Amritsar for the B.C. connection, Mumbai for the urbanism, and Goa for the beaches.

But I could have also seen the amazing Hindu temples in the southeast of the country, or the metropolis of Kolkata, or the ruins of Hampi, or the holy city of Varanasi, and likely have had an equally rewarding time.

Even if it meant I didn’t get 10,000 very silly photos of me and the Taj Mahal.

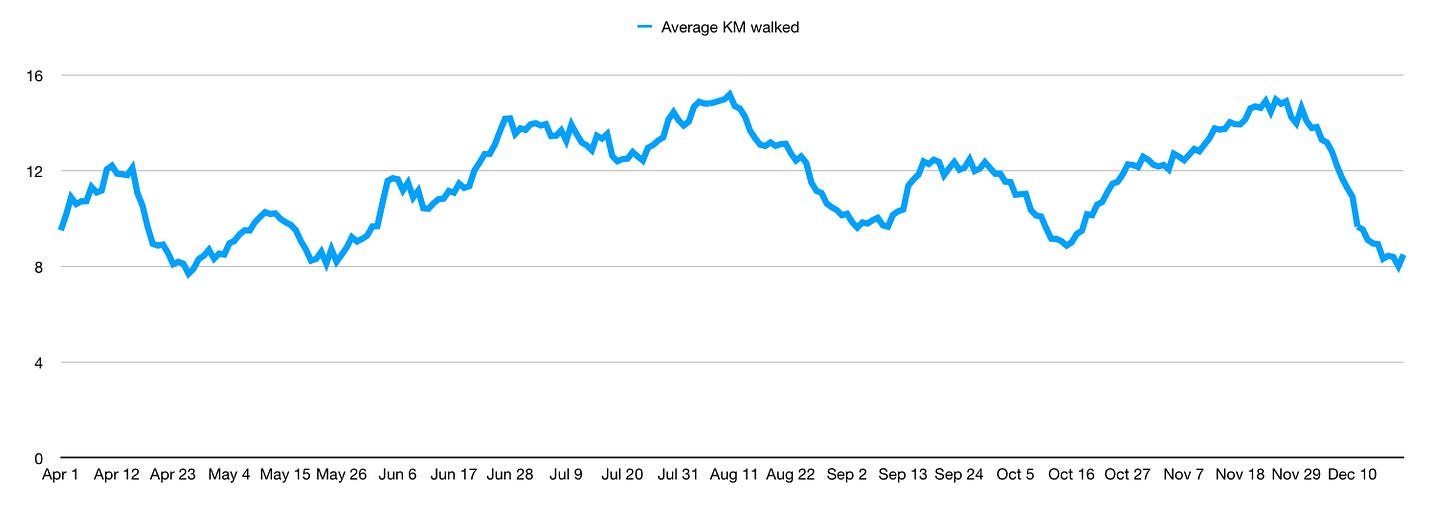

Challenging: walkability. Here is a chart.

That’s a 17-day rolling average of the amount of kilometres I walked every day on this trip, from the beginning of California (cutting out my first two weeks, which were mostly spent on trains in winter) to the end of my 17-days in India.

It is, as data scientists would say, a giant honking dip.

After months of regularly getting 10km of walking in every day, no matter what the country or weather, it proved impossible in India.

The sidewalks are too minimal, the car traffic too great, the size of city is too large and the transit system too non-existent to really explore anywhere on foot that isn’t the immediate place you want to see.

And that’s not even counting the risk of high air pollution or 34 degree heat.

Which is a shame. Walking is not only the healthiest way (smog dependent) of seeing a city, but also of engaging with it on a granular level. You’re forced to directly observe how people live, of how geography and class and green space and infrastructure influence satisfaction, of all those things you don’t get as a tourist if you whisk away in a group bus or private Uber from your resort hotel to the Designated Daily Funtimes Activity.

However, after one day of trying that when I arrived in Delhi, I knew it wasn’t going to be practical. So you make adjustments.

Rewarding: Tuk tuks and tours.

One thing I’ve learned through this trip is that while you will have your own preferences about how to live, it often helps to lean into what a country is best at.

So walking is frustrating in India. You know what I didn’t find frustrating?

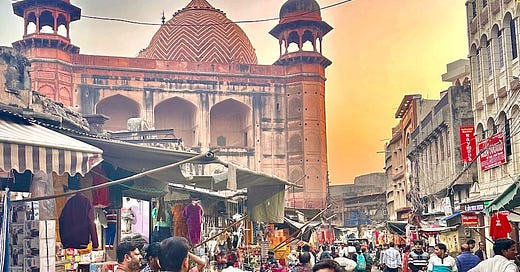

Tuk tuks — or to use the more global term, auto rickshaws, the green and yellow open-air cabs that are ubiquitous in big cities across the northern half of the country.

Aside from being cheap (I didn’t pay more than five bucks for one my entire time there) and plentiful, interacting with the cityscape inside a TukTuk is safer and more visually stimulating than dodging said TukTuks while walking on the side of a street.

In a similar vein, walking from attraction to attraction in India isn’t really feasible, but you know what is?

Hiring a guide for the day to show you around most of the key sites.

For about 50 bucks, you can get a guide and a separate driver to pick you up, get you into the most interesting palaces, have support as you walk through a teeming neighbourhood or two, and get a great meal at a place you otherwise wouldn’t have discovered.

Such tours are plentiful on GetYourGuide or Viator (the two tour apps I’ve used all trip), and generally can be customized if there’s a specific place that you’d like to get to that isn’t on the main itinerary. Plus, because it’s a private tour, you don’t feel as much in a bubble as you would in a group of 10 other tourists.

Again, it’s not how I’ve generally done this trip — aside from the occasional food tours, I’ve only done guided tours for attractions far outside the city, because I want to explore cities at my own pace.

But if you’re a tourist, that’s not where India’s comparative advantage comes from.

Which is why after my first day in Delhi I bought one-day guided tours for there, Jaipur, Agra (Taj Mahal included), and Mumbai. For the rest of the trip, I could enjoy all the interesting places in each of them without stressing over the logistics or traffic.

And that was a good thing, because there are many interesting places.

Challenging: People are everywhere.

It’s a common enough tourist trope to find the poverty in India overwhelming or difficult, yet that wasn’t my experience.

Part of that is because I had been to enough countries with slums and street people and children begging for money that it wasn’t something I needed to mentally adjust to.

But the other reason is that I live two blocks from Vancouver’s infamous Downtown Eastside.

And the truth of the matter is, after 10 months of going to the biggest cities on earth, I still haven’t encountered any neighbourhood with as many clearly struggling homeless people crammed into one highly accessible and visible area as the Downtown Eastside.

That’s painful to write*, and a jarring thing to slowly realize over the course of one’s travels.

On a practical level during the trip though, it has perversely done me well, because if you can walk through East Hastings Street from Abbott to Main without being overly stressed, you can walk through just about any urban street in the world.

(*The somewhat provocative statement comes with certain caveats inherent in the phrasing: there are places I’ve been with more homeless people but are simply spread across a larger area, places with more homeless people in less visible areas, and places with more homeless people who seem to be doing mentally okay, but no places that fit all of those boxes)

So that wasn’t a challenge.

What was a challenge, and what makes India different due to its massive population and many spread out cities, is the sheer amount of different places with people loitering on the street.

I found it another thing my brain needed to be thinking about and requiring extra effort with. Which was the same story as walking, or train logistics, or heat or air pollution, and the end result was just being drained quicker each day than any other country I went to.

Rewarding: People are lovely.

This may be a small sample size, I know. However, I was struck by just how talkative and generous with their time people in India were.

English being ingrained into the national culture via British colonialism no doubt aided to this. Yet even with that caveat, there were less people on the street harassing me than Morocco or Egypt, and more people who seemed to be genuinely interested in my well-being than France or China or other countries where bedside manner is not exactly seen as a national strength.

All of this meant that days in India took extra effort. Yet I looked forward to the effort, because of the things I could see and experiences I could contemplate.

Okay, there was one place in India that didn’t take extra effort: Goa.

Halfway down the western coast of the country, Goa is a region with beautiful beaches and a different vibe, the byproduct of both beach tourists and being a Portuguese colony until 1961.

I took a beautiful train through the jungle from Mumbai to get there, and gave myself three nights to relax, explore a couple of the “popular but not crazy busy” beaches, and start transitioning to the final section of this journey.

After nine months and more than 100,000 kilometres, I was concluding my final country where there would be significant visa or safety concerns. After the logistics of travelling with people in Turkey and China, and having an abrupt cancellation of group travel in Japan, I knew the rest of the trip would be solo. After many months of big cities and temples, I was about to enter a period with plenty of beaches and islands.

I could start seeing the finish line, in other words, with few parts of brain having to think of different challenges ahead, and the number of countries remaining able to be counted on two hands.

To be able to sit on those beaches in Goa and watch the beautiful sunset was extremely satisfying.

To do so while contemplating all the things I had seen and learned and thought?

You’d almost feel enough enlightenment to grow out your hair and get a tattoo.

I so enjoy reading about your travels and will miss these emails in my inbox once you are back in Vancouver. For sure, when you finally publish your book, I will get a copy!

Fantastic observations! Thank you!