52 Countries in 52 Weeks, Part 26: China & Taiwan

In Which I Visit A Big, Beautiful, Important Country And Love Lots Of It, So Long As I Don’t Think About Where I Went Before And After

The first thing I wanted to do when arriving in China was visit the local museum.

True, if you’ve been reading these entries for a while, you might know my enjoyment of museums borders on excessive. However, this one seemed like it would be particularly fascinating.

In 2020 the government shut down the previous exhibits, but in August the museum reopened with a brand new focus, with all the old displays and artifacts on local history gone and replaced with a very different theme.

“National security is the bedrock of a national rejuvenation, social stability is a prerequisite for building a strong and prosperous China” read one large welcome sign, next to displays that offered evidence why Hong Kong had always been part of China.

“National security is closely related to you and me,” read another, around the corner from a display on why crackdowns on protesters were necessary.

At one point, there was an educational cartoon, where a ladybug starts crying after its plan when awry.

“I should have followed the rules,” cried the ladybug.

“Abide by the laws and regulations,” say the other insects.

The Hong Kong Museum of History had changed alright. To the point where even Leni Riefenstahl might have told them to tone it down a notch.

It was an inauspicious start to a very interesting part of my trip.

But it was a helpful reminder that after 37 years of living only in Canada and eight months of travelling across five continents, I had entered a different world.

You know what’s a weird phrase to say?

“I’m not important enough to be taken hostage.”

When I would tell friends and family where I was planning to go this year, China was always the place that raised the most concern.

That was largely due to the two Canadians (Michael Spavor and Koenig) that had been detained by the Chinese government and placed in custody for three years over the fallout from the Canadian arrest of Meng Wanzhou in 2018.

Unlike them, I had not promoted North Korean tourism, or was a diplomat/alleged spy. But I was a journalist for the state-funded broadcaster, one who had done several stories over allegations of Chinese interference in municipal politics, and it did not escape my mind that my chances of avoiding tensions were not the same as a “regular” tourist.

Still, I thought over how much I wanted to see China, and how important it was to the point of my year seeing the breadth of humanity. I thought about how critical China was probably going to be in world politics (to say nothing of the politics of my home country) for the rest of my life.

And I reasoned that I was only applying to stay in China for a couple of weeks, and that the actual worst-case scenario was them refusing my application (which I had to do in Italy, adding the complications), denying me entry at the border, or telling me to leave.

None of those things happened. Still, throughout my trip I had those thoughts come up multiple times a day during what is probably the most intrusive part of the China Experience: the passport check.

Prior to China, I could probably count on one hand the number of passport checks outside of border crossings and hotel check-ins.

During China? Taking the train. Going to a museum. Going to a show. Purchasing a ticket for pretty much everything required handing over your identification to an agent, them scanning your picture, and waiting a couple of seconds before being given the thumbs up.

By the 20th or 25th time, you can’t help but thinking about what they’re looking at and what information they’ve collected. You also start thinking about all the surveillance cameras, how quiet places are when the old men aren’t aggressively spitting onto the ground, how pristine everything is outside of the lingering odor in the air.

It was all so orderly and regimented.

Was it also joyless, or was I just extrapolating?

I spent 18 days in Hong Kong and Mainland China, doing essentially a circle route of the biggest or most beautiful places in the eastern half of the country: north to Shanghai and Beijing, west to Xi’an and Chengdu, back south to the iconic geographic features of Zhangjiajie and Guilin, before finishing in Guangzhou.

Logistically, it was a breeze, owing to the massive high-speed rail network the country has created out of cloth over the last two decades.

Every day, there are dozens and dozens of trains going 200 to 300 kilometres across the country, crisscrossing areas the width of British Columbia in a couple of hours, going up and through mountains, stopping in gigantic modern train stations on the outskirts of cities big and small, all for 5 to 200 bucks, depending on the length of trip.

It was genuinely impressive, and probably the most unambiguously positive example of the many displays of China’s mix of autocratic government and technical prowess.

The rest of navigating the country was more difficult, but still manageable.

Paying for most things or using the internet requires you to download two specific apps (WeChat and Alipay, please do not ask me to describe which one you need for which purposes), which add to the feeling of being dependent on higher authorities to a much greater extent than other countries.

The number of people in service and hospitality industries speaking English was a fair bit less than Japan and South Korea, requiring an extra layer of patience.

And one is reminded constantly how big the country is: not just in size, but in population, with 1.6 billion people, making even a “mid-sized” city bigger than anywhere in Canada outside of Toronto or Montreal.

So getting places take time, patience is required, and you’re very aware you’re in a one-party state where you could be tracked at any time.

But was it worth it?

Oh goodness yes.

Here’s the best way I can describe it: a trip to China combines the civilizational wonders of Egypt, the wealth and attractions of the United States, and the efficiency of Germany.

You could spend entire days in Beijing geeking out on the treasures of the Forbidden City or the splendor of the Summer Palace. Do your best Blade Runner cosplay in Hong Kong. Explore mountains and desserts and small cities in the middle of the country for weeks on end.

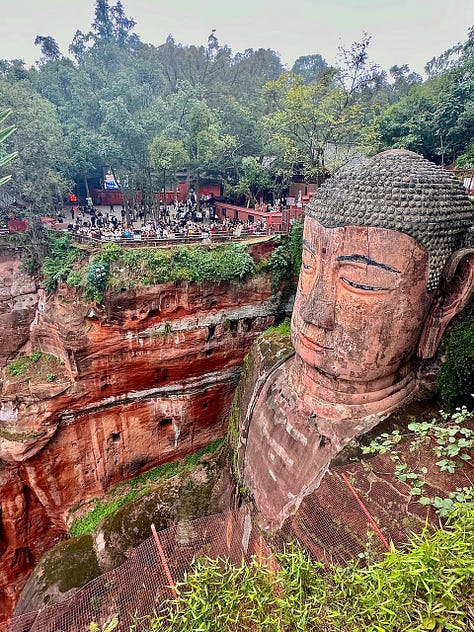

I went to amazing food markets in Xi’an and Chengdu, had otherworldly hikes in Zhangjiajie, and a lovely boat cruise around the karst pillars in Guilin.

And then there were the pandas! Dozens of them, sleeping and eating and slowly ambling, all in the remarkable Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding that I made a somewhat last-minute decision to take a detour to, because at a certain point I was like “I really really want to see lots of pandas,” and what’s the point of taking a year to travel the world if you can’t indulge in that sort of silly joy?

Once I got used to the specific apps, doing things was honestly just as easy as my trips through Germany or the United Kingdom.

Being in China is being in a different world, a world where all the geography and technology and culture is just different enough to take notice, a world where Lotso, the villain in the 2011 film Toy Story 3 is strangely one of the most popular toys in the country.

Once you get used to that world, there’s a lot (as a tourist in the short-term) to like about it.

Plus, the sheer amount of money and might allows for displays and attractions that cater to pretty much every whim imaginable.

Which is how in Shanghai I ended up at the five-storey tall museum dedicated to urban planning.

There were high-tech informative displays about official community plans and multi-modal transportation schemes. Interactive games designed to teach people about clean energy. Videos and timelines and so many interesting ways of explaining an incredibly dry and nerdy subject at a scope that is simply impossible to imagine in a Canadian city.

It made me crack many jokes about how Vancouver’s version would have a section dedicated to the joys regional planning in a patchwork system of 21 municipalities (I truly cannot help myself), but it was also just plain fascinating.

Ironically, Shanghai suffers from the same planning issues as many of the megacities I’ve been to: transit systems that unspool like spaghetti in random directions, too much congestion and not enough green space, issues with air pollution (although China has made large leaps on this), a convenient city to live in but one that has struggled for decades to solve issues that “liveable” great cities take for granted.

And the urban planning museum made no note of the newer cities across China filled with block after block of identical beige apartments.

Money and not having to deal with pesky public accountability can make building cities easier.

At the same time, the inherent tensions and tradeoffs around supply, demand and limited geography remain.

Was the Great Wall the best ancient monument I’ve seen?

My day at — or rather, on — the wall was one of the most emotionally impactful this entire trip. Some places fail to live up to the imagined vision you’ve had in your head since a child, but the Great Wall was not one of them.

This leads to a more important question, one arguably as important as the Great Wall of China itself: where does it rank in my ranking of world monuments?

And the answer is 2nd. Next to the Great Pyramids. Because in my heart, I’m a giant normie.

That could change when I more seriously consider the Monument Ranking for my Very Serious Book (coming out in early 2026!), because I could change my opinion or see something amazing in Country 51 or some mystery third option.

However, let’s consider more carefully/whimsically what makes a great monument, in what will sort of be a draft 50-point rubric to help focus my feelings on this.

Historical importance (20 points): Why was it created? How long ago was it built? What sort of an impact has had over the decades or centuries, either in a tangible or cultural sense? These are thoughts in the back of your head (and at the front of the Lonely Planet article you scanned a week before your flight) as you look at this creation.

(The Great Wall does enormously well on this measure in terms of its origins and impact, even if it was *only* built in 14th century)

2. Beauty (15 points): History, shmistory — does it look beautiful? Or provoke wonder? Or cause people to debate whether she’s smiling or not for centuries?

Appreciating the history of a monument is important, but also a bit of an intellectual exercise. But if it’s visually stimulating, the experience is much more well-rounded to the senses, and ensures you aren’t reliant on listening to your overly excited 50something dad as he talks about the importance of this First World War battlefield or the engineering prowess required to build these canals.

(Again, the Great Wall: it’s very great. Very big. More than that, the way the wall cuts along the mountain range, and how you can see it dip and rise and turn over the skyline, unencumbered by any other hints of civilization…there are legitimately few things like it)

3. Crowds (10 points): Crowds suck. Telling someone “you have to arrive there three hours before it begins if you truly want to enjoy it” is not actually good. The act of appreciating the history and beauty and wonder of the monument is much harder if you’re surrounded by hundreds of sweaty tourists with jutting iPhones and awkwardly fitting hats.

Plus, if part of your brain is trying to imagine what it was like to see this thing when it was created, it becomes nigh impossible if the site is swarming with people.

There is a paradox to this of course: the more beautiful and historically significant a thing is, the more people will want to see it. After going to so many of these sites over the past 10 months though, I’ve concluded that being able to navigate this challenge is one of the most critical parts to ensuring a great monument is truly appreciated.

(This might be the Great Wall’s secret weapon — there’s a part of it quite close to Beijing that’s very flat, and consequently gets the bulk of families and Chinese tourists. But the Mutianyu section, which is only about 90 minutes outside of the city, had only a hundred people or so for every kilometre, giving plenty of space to slow down and reflect and imagine the area as it once was.)

4. Interactivity (5 points): This is a secondary concern compared to the others, but I think it really matters — are you doing anything at the monument besides standing still and taking a photo?

Because that’s an awful lot of time and money to spend for a limited experience, to say nothing of the fact that Google Streetview exists.

Again, a tension here: the more interactive a monument is, the more preservation becomes an issue, and its authenticity might get reduced, which is why large portions of the Great Wall have been replaced over the years, creating a Ship of Theseus dilemma.

Still, to see the wall, climb up on a gondola to the wall, walk on the wall, hide in the turrets on the wall, and then stop on the wall, and close your eyes on the wall, and taking the moment in?

In a year full of emotionally transcendent experiences, it created an extra layer of special that I will always remember.

What a fun ranking that was!

now let’s get back contemplating the beauty of the world contrasted against the hubris of man

Two weeks after I left Hong Kong, 45 democracy activists were sentenced to up to 10 years in jail, the culmination of several years of the Chinese government imprinting their power and inevitably of one-party rule with no freedom of speech on the island.

A week after that, I was in Taiwan, which could well go the way of Hong Kong…and some might call that a geopolitically optimistic scenario.

It was not on my original list of places to go — I went because it worked well as a convenient stop point between two countries where I faced potential visa issues — yet I’m very glad it came together.

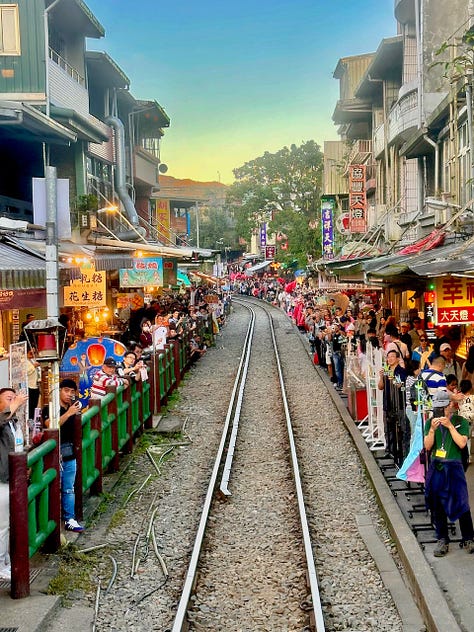

The geography is beautiful, with gorgeous hikes and cute mining towns next to rivers within easy access of Taipei.

The cuisine was awesome, with a great mix of savoury and sweet foods and the best night market scene I’ve seen on this trip.

Taipei’s transit system is efficient and intuitive, its streets are energetic without being overwhelming, the economy is strong and the people are friendly.

And all of that feels so tenuous, given China’s increasing signals of wanting to take over what it believes is its rightful territory.

As Noah Smith wrote a few weeks ago:

“Spend a few days in Taiwan and tell me honestly if there is anything wrong with it — some terrible injustice that needs to be corrected with saturation missile strikes and invasion fleets. You cannot. The people here are happy and wealthy and productive and free. The cities are safe and clean. There is no festering racial or religious or cultural conflict,no seething political anger among the citizenry. Everyone here simply wants things to remain the same.

And yet there is a good chance they may not be granted that wish.”

Of course, China is one of the world’s most important empires, and is next to a country that has a similar culture but is much smaller in population and military might.

For centuries, such a dynamic often resulted in takeover through war, or a torrent of treaties that slowly destabilized and reduced the sovereignty of the smaller country to the point where annexation was a mercy kill.

The last few decades had been an exception to that. Now, turning points to that era of history seem to be accelerating.

Today’s Ukraine might be tomorrow’s Taiwan, and it is hard not to travel this year and reflect on the history of so many places and wonder if next week it might be Canada.

China was amazing. I’m so glad I went.

And yet I wonder how likely it is that I’ll ever return.

What a transformational journey you’ve been on. Thanks for sharing. These are truly interesting reads. I read that Noah Smith article, btw (I’m a subscriber too.) it was one his darker ones, although there have been a few more like it since. Sign of the times I guess. Happy trails, my friend.

Justin, I highly recommend Su Bing's 400 Year History of Taiwan (English edition is available). It reveals how a unique Taiwanese identity has emerged after waves of colonization. I was intrigued to read that the leaders of Imperial China actually held Taiwan in great disdain. They saw it as a land of pirates and a place that was not connected to China. Immigration from Taiwan to China was banned well into the 19th century, according to the book. Now, Taiwan is supposedly a long-lost province called "Chinese Taipei". I wish the Canadian media would tell this story more often to demonstrate how tenuous China's claims really are. Perhaps you can start doing this upon your return. I've enjoyed your dispatches from around the world.