52 Countries in 52 Weeks, Chapter 12: Germany

In Which I Enjoy A Country’s Trains, Games, Beers, And Museums

A large flag covered the Scotsman from neck to ankle. He was red in the face, from what could only be surmised as the result of an afternoon of drinking and talking. And now, walking towards a group gathered in a large public square, he had a grievance to air.

“Your beer is no good!” he said to the Germans.

It was two hours before the start of the quadrennial Euro football championship being hosted by Germany. I was in Munich for the first match between Germany and Scotland, where tens of thousands had descended on the city to take in the revelry and championship kickoff.

It had created a day-long pregame rally in squares across the city, with steins and bottles cast on the ground long before the match was to start, with distinctive Scottish kilts nearly outnumbering German flags in some beer gardens.

And this man, already half in the tank, was taking umbrage. Mostly in jest.

“It’s filthy!” he said, getting closer to them now, raising the bottle high, a look of mischief on his face.

To which one of the Germans had a quick reply.

“That beer? It’s from the north! Of course it’s no good!”

He raised his own bottle.

“Take this, it’s much better.”

The Scotsman took the beer, had a sip — maybe a bit more than a sip — and then toasted his newfound friends.

A silly, lovely example of the way sport, at its best, brings people together.

And then they all departed the steps of the Feldherrnhalle, a place that 101 years before was the infamous site of a battle where leaders of a then-marginal extremist party were defeated after a failed beer hall putsch.

Comparisons between Euro the football tournament and Europe the geopolitical entity happen every four years, though were heightened this time given the French, British and EU elections that showed a particular anti-status quo bent.

While anxieties linking the two were real (particularly in France) on the ground it all seemed abstract. People from across the continent came to Germany to cheer and to party (though not exclusively in that order), and the atmosphere in and outside the stadiums was always jovial.

I watched one match in person — a Czech vs. Georgia battle in Hamburg that ended in a draw — and several others in beer gardens that ranged from dozens to hundreds of people.

I was always going to spend some time in Germany, given its size and importance. Going for the start of Euro was mostly to enjoy the rush of emotions that come with sports at their highest skill level, but there was a little bit of journalistic observation as well.

In 2026 Canada will be one of three hosts for the World Cup, and Vancouver will host seven games. The route to getting there has been somewhat bumpy, as B.C. originally declined to pay the costs associated with being a host city, only to reverse course after intense lobbying.

Since then, Vancouver Mayor Ken Sim has become a big champion of the city’s involvement, saying it was the equivalent of “30 or 40 Super Bowls” and defending the approximately $500 million cost to host the matches. When I return home, it will remain an ongoing debate whether the cost will be worth the return, and if there will be an explosion of people and excitement for the matches.

But my experience in Germany didn’t convince me it will be the slam dunk (or penalty kick?) that Sim thinks.

To be sure, when Germany was playing Scotland in Munich, the city lit up at a level equivalent to when Vancouver hosted the 2010 Olympics. The activity on the streets and energy in the air was palpable throughout the city, the beer gardens were packed, and the buzz in the bars lasted long after the 5-0 shellacking of Scotland ended. And in cities big and small, town squares turned into watch parties for all of Germany’s games, with plenty of people turning out.

The matches in cities where Germany wasn’t playing though?

There was an energy, to be sure, the type that only comes when tens of thousands of strangers descend upon a city in synchronized colours and chants.

Once you got outside the stadium and the main bars though, the atmosphere was somewhat muted: Germans were excited to cheer on Germany and to open their cities to the world, but if the match didn’t involve them, it didn’t dominate the rhythm of the city.

It was more like a big concert was happening — something a bit more than a regular arena show, but much less than Taylor Swift or Beyoncé, if that makes sense.

However, there were two key elements of Germany that played a big role in how people from other countries enjoyed Euro, elements that are not particularly prevalent in my country.

One, beer gardens. And two, trains.

From Munich to the Rhineland, from Berlin to Hamburg, you could see trains with plenty of seats filled with jerseys from across the continent, as people hopped from one city to another to watch their country in action.

It was remarkably easy to do so, as Germany has an incredibly extensive rail networks: 33,000 kilometres worth of tracks, 3 billion passengers a year (4th most in the world), with a range of public and private and high-speed and commuter options to suit just about any need.

I took eight trains while in Germany, going Munich to the medieval village of Rothenburg, followed by Bamberg, Berlin, and Hamburg, before heading north to Denmark.

(A quick sidenote to say that Rothenburg on der Tabuer is about the most fairy tale village you can find in Europe…but due to the mass of visitors during the day, is really only special after 5pm or before 9am, when you can wander the streets and walk the ancient walls in a setting more emblematic of the how the population lived there for hundreds of years before it became a tourist trap.)

There were two particularly striking things about the train experience, even compared to other European countries I’ve been to so far.

The first was just how extensive the train system was. I would be waiting in cities of less than a million people, and the posted train schedule for that day would go on for a page. Towns of 10,000 people are connected to cities of 100,000 people on slow trains that come a couple times each day, towns of 100,000 people are connected to regional centres on faster trains that come every few hours, and regional centres are connected to big cities on high-speed lines that come every hour.

All very straightforward, efficient* in the best German sense of the word, and it made it easier to understand why the BBC focused an entire episode of a reality travel show around my home province’s lack of trains and patchwork of limited regional bus services.

(Update: while my trains were on time, that wasn’t the case for plenty of other people. Still, the scope of the system is mighty impressive.)

And the second striking thing was just how open and trusting the system was: there were no fare gates, no additional reservations to secure a seat. If you had a rail pass, you just hopped on a train and went, with on-board ticket checks happening about 20 per cent of the time.

For such a large system, there was such a small amount of security and front-facing bureaucracy, in a way that seems anathema to Canada.

That extended to the drinking culture as well: beer gardens everywhere, including next to playgrounds, bars encouraging people to have their pint on the street, no ticketing or stamps to be seen.

(A similar laissez-faire attitude also permeated the most fascinating place I saw in Berlin, a giant abandoned airfield that has turned into a minimalist park which people have voted to preserve in spite of pressure to develop it for housing)

There was a different level of personal responsibility and paternalism than I’m used to, and made for a stress-free way for fans to enjoy an international football tournament: take a train to the city your country is playing at, find a beer garden, cheer them on, repeat at your leisure.

The vibe for Vancouver’s games will be different. The fan zone will not be at the centre of the city, but on the far east side. The beer culture will be heavily regulated, memories of a riot 13 years ago still dictating city policy. Fans from other countries will find it much harder to travel from place to place to cheer on their team.

Yet, I suspect they won’t be disappointed. After all, the SkyTrain goes right to the stadium, the weather is temperate, the mountains are stunning, and the sushi is fresh and affordable.

And best of all, being tourists, they’ll never have to think about the local housing market.

As this trip has progressed, I’ve found myself increasingly fascinated by museums: what topics each country focuses on, how they portray a country’s story, the tone in which and convey information.

Not surprisingly, Germany offered a fruitful field of study.

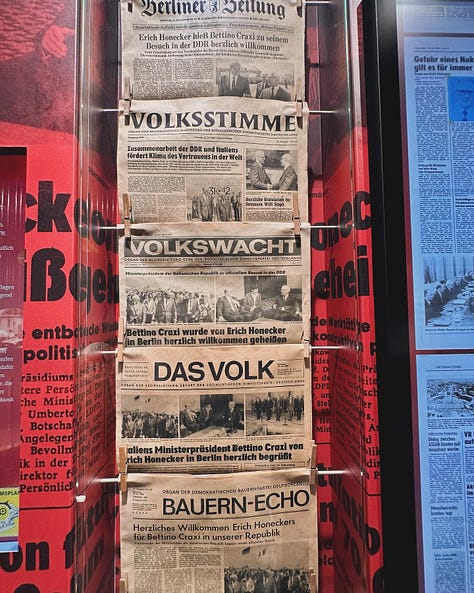

There were outstanding museums about design and technology and East Germany and medieval torture and ancient ruins and video games and everything in between, all done with large budgets and plenty of care.

(A particular shoutout to the East Germany museum, which had a number of sublime tactile opportunities — you could get into a vintage mass-produced car, explore a 1980s flat, and open dozens of little cupboards to reveal different facts about the government. It showed that “interactive” doesn’t have to mean “spend tons of money on a touch screen app that will appear dated in three years.”)

Most significantly, the degree to which museums were upfront about the countless atrocities of the Nazi regime was bracing, particularly in places that could have conceivably avoided the subject.

In Munich’s museum of technology, sections on airspace went into detail on the slave labour required to give German its aeronautic advances. In traditional art museums, there were displays about the looting of treasured works in other cities. In the transport museum, time was taken to explain how companies changed their priorities to cooperate with the Third Reich’s objectives.

Even a family-oriented museum centred around elaborate miniature worlds from different eras of Berlin had a large section with a burning Reischstag, the city in ruins, including a Führerbunker with a stooped Hitler having just shot himself.

The degree to which the displays about the Nazis bluntly displayed what happened, without lengthy explanations or contextualizations, shouldn’t have been such a surprise. But to see it laid out — in the case of the Topography of Terror, literally, with the actual documents and memos they published to legally justify decisions — made a bigger emotional impact than what I was expecting.

At the same time, Germany struggles with a lot of the same questions over appropriation and purpose and budget that a lot of museums face these days.

Perhaps Berlin’s most famous museum, the Pergamon, is in the midst of a 14-year renovation, which has led some to question the point of holding onto other country’s archeological treasures if they can’t been seen for a generation.

A few hundred metres away sits the Humboldt Forum, which houses a number of different museums in a palace that cost nearly a billion dollars, igniting controversy. Within the complex there’s a tonal clash, with displays showing artifacts from German colonies in the South Pacific saying very little about the exploitation of the time, while an exhibit on modern Berlin focuses heavily on racism and slave labour in the fashion industry.

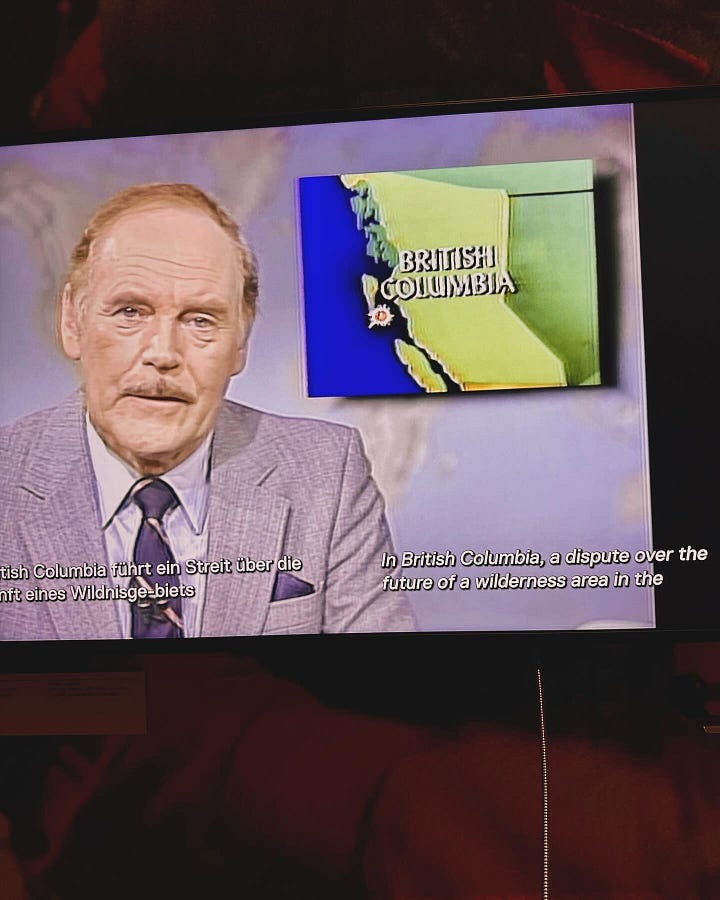

And in the middle of it all, there was an exhibit that came from my home province.

Presented in collaboration with the Haida Gwaii Museum, Ts’uu - Cedar examines the history and culture of the Haida people, the evolution of their relationship with the Canadian government and colonizers, and the legal battles to get back control of their ancestral lands.

There was artwork and text, maps and documents, Bill Reid carvings and modern interpretations of Haida life displayed in manga comic form.

It was well presented, while activating fascinating and conflicting thoughts in my head as I watched others navigate the exhibit.

They were probably learning about the story for the first time, whereas I had witnessed its evolution over decades. It was a story about a province I love so much, but from the perspective of people that never consented to be part of it.

And in the middle of it, there was a TV news piece one could watch. It was from a middle-aged CBC reporter in the mid 1980s, with a story on the logging conflict, the anchor introducing the piece by saying it could take decades to resolve.

Journalism is the first draft of history. But it can be the second and third draft, sometimes preserved in a museum thousands of kilometres away, the present echoing the past, and all the ramifications and responsibilities that come with it.

That news reader was the esteemed George Mclean. over a decade in Vancouver reading the news (TV and radio) rowing a boat into the middle of English Bay to cover a story.

And a (slightly British-accented news reader for documentaries galore (Massey Tunnel anyone) seen in many BC schools)

We were sad when he went to Toronto. He knew everything about BC, and unlike McElroy, corrected himself when making mistakes/gaffes. Many decades reading the National.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_McLean_(journalist)

Great writing! You bring your travelling experiences to life in ways your reader can feel like they are there. Continued safe travels.